Effects of Dietary Cholesterol on Serum Cholesterol a Meta-analysis and Review

Dietary Cholesterol, Serum Lipids, and Heart Disease: Are Eggs Working for or Against You?

Department of Nutritional Sciences, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269, USA

*

Writer to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Received: 13 Feb 2018 / Revised: 24 March 2018 / Accepted: 27 March 2018 / Published: 29 March 2018

Abstract

The relationship between blood cholesterol and heart disease is well-established, with the lowering of serum depression-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol being the principal target of preventive therapy. Furthermore, epidemiological studies written report lower risk for heart disease with higher concentrations of high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol. There has too been considerable interest in studying the relationship between dietary cholesterol intake and middle affliction risk. Eggs are i of the richest sources of cholesterol in the diet. However, large-scale epidemiological studies have found only tenuous associations between the intake of eggs and cardiovascular illness run a risk. Well-controlled, clinical studies show the affect of dietary cholesterol challenges via egg intake on serum lipids is highly variable, with the majority of individuals (~2/3 of the population) having only minimal responses, while those with a meaning response increase both LDL and HDL-cholesterol, typically with a maintenance of the LDL/HDL cholesterol ratio. Recent drug trials targeting HDL-cholesterol have been unsuccessful in reducing cardiovascular events, and thus it is unclear if raising HDL-cholesterol with chronic egg intake is benign. Other important changes with egg intake include potentially favorable effects on lipoprotein particle profiles and enhancing HDL part. Overall, the increased HDL-cholesterol normally observed with dietary cholesterol feeding in humans appears to also coincide with improvements in other markers of HDL part. Withal, more investigation into the effects of dietary cholesterol on HDL functionality in humans is warranted. In that location are other factors found in eggs that may influence risk for heart disease by reducing serum lipids, such as phospholipids, and these may besides alter the response to dietary cholesterol found in eggs. In this review, we talk over how eggs and dietary cholesterol affect serum cholesterol concentrations, equally well equally more advanced lipoprotein measures, such as lipoprotein particle profiles and HDL metabolism.

ane. Introduction

Cardiovascular affliction (CVD) contributes to more than 17 meg deaths per year globally, which accounts for nearly half of all deaths from non-communicable diseases [one]. Cardiovascular disease is primarily caused by atherosclerosis, a chronic inflammatory disease of the arteries in which the deposition of cholesterol and fibrous materials in artery walls forms a plaque or lesion [2]. Key adventure factors that acquaintance with the number of atherosclerotic CVD events include the total concentration of cholesterol found in the blood, also as the cholesterol institute in private lipoprotein subclasses [3]. Serum concentrations of low-density lipoprotein -cholesterol (LDL-C) and loftier-density lipoprotein -cholesterol (HDL-C) have contrary effects on CVD take a chance, consistent with the role of LDL particles in the promotion of, and HDL particles in the protection against, atherosclerosis [four,5].

2. Cholesterol, Eggs, and Eye Illness

2.1. Relationship between Dietary Cholesterol and/or Egg Intake on Adventure for CVD in Observational Studies

The Framingham Heart Report was 1 of the first studies to show a human relationship betwixt serum cholesterol and center disease, and it was hypothesized that dietary cholesterol was a modifier of heart disease through furnishings on serum lipids, even though no such clan was observed at the time [6,7]. This hypothesis was consequent with evidence from animal studies, such as the seminal piece of work past Nikolai Due north. Anichkov in rabbits in 1913, showing large doses of cholesterol in the nutrition markedly induced atherosclerotic plaques in aortas [8]. Even with these early studies, it was clear that there were species-specific differences in the atherosclerotic response to big doses of dietary cholesterol, with rats existence markedly more resistant than rabbits and guinea pigs [eight]. The average intake of dietary cholesterol in U.S. adults is typically between 200–350 mg/day, depending on gender and age grouping [ix]. Eggs are a major source of dietary cholesterol in the typical Western diet; one large egg yolk contains approximately 200 mg of cholesterol. The consumption of eggs and egg products contributes most a quarter of the daily cholesterol intake in the U.Southward. in both children and adults [ten,11]. Saturated fat is known to strongly increase serum cholesterol, and eggs, which are relatively low in saturated fatty, only contribute virtually 2.5% of total saturated fatty acid intake among U.Due south. adults [11].

Early observational studies demonstrated a link between dietary cholesterol and gamble for CVD [12,13]; however, these initial studies failed to business relationship for many confounding variables that may limit their findings, such as other dietary and lifestyle factors. More recent epidemiological studies typically show a lack of clan between dietary cholesterol and/or egg intake and CVD risk in the general population [14,fifteen,16]. Yet, there does appear to be a more consistent human relationship between egg intake and CVD in diabetics [14,15], however, this is not e'er found [17]. Interestingly, this risk in diabetics may exist related to the phosphatidylcholine content of eggs [eighteen], and not the cholesterol since dietary cholesterol is shown to be more poorly captivated in obese and insulin-resistant populations compared to lean individuals [19,20,21]. Phosphatidylcholine intake has been linked to the gut microbial-dependent generation of trimethylamine North-oxide (TMAO), a metabolite shown to promote atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic mouse models and associated with CVD adventure in human accomplice studies [22,23]. Even so, the consumption of ii–three eggs per twenty-four hours was not associated with increases in fasting TMAO concentrations in healthy, young adults [24,25], while postprandial TMAO concentrations in the plasma of healthy men were constitute to be markedly lower after egg intake than fish intake, a direct source of dietary TMAO [26]. The touch of egg phospholipids on CVD and TMAO concentrations in humans is probable complex and requires farther research [27,28]. Berger et al. [29] conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 17 accomplice studies examining the human relationship between dietary cholesterol and CVD. Dietary cholesterol intake was not constitute to be significantly associated with either eye disease, ischemic stroke, or hemorrhagic stroke.

2.two. Serum Cholesterol Responses and Adaptations to Cholesterol Intake

Early on dietary recommendations assumed that increasing dietary cholesterol intake would lead to an increase in cholesterol in the claret, which over several decades would promote the evolution of heart illness. Yet, this is an oversimplification since the serum cholesterol response to dietary cholesterol is much more complicated. Humans can produce cholesterol endogenously and most of the cholesterol in the body comes from biosynthesis [30,31]. Only nigh 25% of serum cholesterol in humans is derived from the diet while the rest is derived biosynthesis. The average seventy kg adult synthesizes about 850 mg cholesterol/day. If this private was to eat 400 mg/day of dietary cholesterol and absorb lx% [32], that amounts to simply 22% of cholesterol handled in the torso coming from the diet (240 mg from the nutrition out of a full of 1090 mg); furthermore, these numbers are skewed fifty-fifty more towards cholesterol biosynthesis in overweight and obese people [19,20,21]. Cholesterol balance is affected by synthesis rates of cholesterol and bile acids, also equally their excretion from the body. Sterol balance studies have shown feedback inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis and increased excretion of bile acids with high cholesterol diets [33]. Cellular cholesterol biosynthesis is tightly regulated by a transcriptional program coordinated by sterol regulatory element-binding protein-two (SREBP-2) [34]. SREBP-ii transcriptional activity increases when cellular cholesterol is reduced to upregulate the expression of genes encoding proteins involved in cholesterol biosynthesis, such as hydroxymethylglutaryl CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase (HMG-CoAR) [34]. When cellular cholesterol is increased, both cholesterol biosynthesis and lipoprotein uptake are reduced via feedback inhibition. In this condition, SREBP-2 activity is reduced to attune factor expression, while the degradation of HMG-CoAR poly peptide is enhanced in a post-translational manner [34].

Results from controlled feeding studies have been used to formulate predictive equations on the serum cholesterol response to dietary cholesterol [35]. These equations consequence in estimates ranging from two.2–4.5 mg/dL changes in serum cholesterol per 100 mg/24-hour interval change in dietary cholesterol [35]. More than recent equations predict a 2.ii–2.5 mg/dL change in serum cholesterol per 100 mg dietary cholesterol, equivalent to virtually a 2–3% change in serum cholesterol per egg [35]. This event is relatively weak compared to modifying other dietary components, such equally saturated fat acids [36,37]. In fact, equally early on on every bit the 1960s, it was clear that dietary cholesterol was not a major factor in regulating serum cholesterol. Dr. Ancel Keys, a pioneer in studying diet-CVD relationships, stated in 1965, "For the purpose of controlling the serum level, dietary cholesterol should not be completely ignored but attention to this factor lone accomplishes little" [38]. Such small changes with dietary cholesterol intake are probable related to feedback command mechanisms that can limit our power to blot and synthesize cholesterol, as well as increase the amount that we excrete from our bodies [31,39]. Thus, most individuals accept a marginal modify in serum cholesterol in response to dietary cholesterol due to feedback regulation of whole body cholesterol stores. This is demonstrated by a rather farthermost case, of an 88-year old man who apparently compulsively ate 20–30 eggs/day and had normal serum cholesterol (~200 mg/dL) [40]. This man was reported to absorb merely a small fraction (xviii%) of the dietary cholesterol that he consumed and had twice the mean rate of bile acid synthesis as compared to control study volunteers [40]. Not everyone reacts the same way to dietary cholesterol intake, as the response is highly variable and depends on both genetic and metabolic factors [31,41,42]. Numerous clinical trials conducted in children [43], immature women [44], men [45], and older adults [46] take demonstrated differences in serum cholesterol responses (hyper- vs hypo-responders) when consuming an additional 500–650 mg of dietary cholesterol from eggs for at least 4 weeks. The majority of the population (ii/3) has no or just a mild increment in serum cholesterol when they consume a large corporeality of dietary cholesterol. These individuals are classified as hypo-responders or compensators, in that they tin compensate by reducing cholesterol biosynthesis, assimilation, and excretion [31,39]. On the other mitt, a small-scale proportion of the population has a much larger increase in serum cholesterol (≥two.iii mg/dL increment in serum cholesterol in response to 100 mg dietary cholesterol)—these individuals are classified equally hyper-responders or non-compensators.

three. Dietary Cholesterol from Egg Intake and Lipoprotein Metabolism

three.1. Effects of Dietary Cholesterol from Egg Intake on LDL-C, HDL-C, and the LDL-C/HDL-C Ratio

Berger et al. [29] examined the serum lipid responses to dietary cholesterol across xix intervention trials. Dietary cholesterol intake, which came mostly from eggs, was shown to significantly increase both serum LDL-C (6.vii mg/dL net change) and HDL-C (3.2 mg/dL net change), resulting in just a marginal increment in the LDL-C/HDL-C ratio (0.17 net change) [29]. Using the LDL-C/HDL-C ratio may provide an estimate of how much cholesterol is delivered to plaques via LDL, too as potentially how much is beingness removed past HDL [47]. An LDL-C/HDL-C ratio <2.five is considered optimal based on individual lipoprotein recommendations, while evidence suggests in that location is an increase in the gamble for cardiovascular events in a higher place this level in some populations [47,48]. Table ane summarizes results from clinical studies examining the effects of added dietary cholesterol via egg intake on serum lipids during weight maintenance in healthy and hyperlipidemic populations. In children and adults with normal cholesterol levels, consumption of 2–4 eggs per day vs. yolk-free egg substitute significantly increased both LDL-C and HDL-C in most studies, with no change in the LDL-C/HDL-C ratio [41,43,44,46]. Healthy men who were classified as hyper-responders (15 out of 40 participants) did evidence a meaning increment in the LDL-C/HDL-C ratio with the consumption of three eggs per twenty-four hours for 30 days, however, the hateful ratio (two.33 ± 0.80) was notwithstanding within the optimal range of <2.5 [45]. Like responses were observed in hyperlipidemic adults; consuming two eggs per day resulted in elevated HDL-C without a change in LDL-C in hypercholesterolemic adults, while there was an increase in both LDL-C and HDL-C in combined hyperlipidemics (elevated serum cholesterol and triglycerides) [49]. In older adults taking statins, consuming either ii or four eggs per day did non significantly increase LDL-C, whereas HDL-C was increased with both doses of eggs [50].

Since there appears to be a relationship betwixt dietary cholesterol and/or egg intake and heart disease in diabetics, exercise individuals with insulin resistance and/or diabetes have a more than exaggerated lipid response? Table 2 summarizes results from clinical studies examining the effects of added dietary cholesterol via egg intake on serum lipids during weight maintenance in insulin-resistant and diabetic populations. Overall, those with insulin resistance and/or diabetes seem to have a weaker serum cholesterol response to eggs relative to leaner, insulin-sensitive individuals; consequent with the reduced dietary cholesterol absorption efficiency observed in obesity and metabolic syndrome [nineteen,xx,21]. Knopp et al. [41] compared the consumption of iv eggs per solar day vs yolk-free egg substitute on serum lipids in both insulin-resistant lean individuals (IR) (mean BMI: 24.5 kg/m2) and insulin-resistant obese individuals (OIR) (hateful BMI: 31.five kg/gtwo). The 28-mean solar day consumption of eggs resulted in increases in both LDL-C and HDL-C in the IR grouping compared to egg substitute, while only HDL-C was significantly increased in the OIR group. Furthermore, clinical studies in diabetics showed that consuming ane–ii eggs per day for 5–6 weeks did not affect LDL-C or HDL-C relative to control groups defective egg consumption [51,52].

Eggs are nutrient-dense, and relatively low in calories and carbohydrate, and thus, may exist considered a good food choice for weight loss diets. Table 3 summarizes results from clinical studies examining the effects of added dietary cholesterol via egg intake on serum lipids during weight loss. Overall, the few weight loss studies conducted in overweight [53,54], insulin-resistant [55], and diabetic populations [56] have found no changes in LDL-C, with most increasing HDL-C. This led to most showing no effect on the LDL-C/HDL-C ratio [54,56], while i report showed a decrease in this ratio [55].

three.2. Effects of Dietary Cholesterol from Egg Intake on Lipoprotein Particle Characteristics

Although LDL-C and HDL-C are established indicators of CVD gamble, lipoprotein particle characteristics, such every bit particle diameter and concentration, may also influence disease run a risk. For case, having a greater plasma concentration of particles of the large HDL subclass is strongly associated with lower risk for CVD, while the concentration of smaller HDL particles is less protective [57,58]. Conversely, the concentration of large LDL particles is only weakly associated with CVD risk, while pocket-size LDL concentrations are strongly positively linked with CVD [58]. The bear on of smaller LDL particles on CVD is thought to exist related to their greater susceptibility to oxidation compared with larger LDL particles [59]. Oxidized LDL is a major commuter of atherosclerosis development and CVD [threescore]. Table 4 summarizes results from clinical studies examining the furnishings of added dietary cholesterol via egg intake on lipoprotein particle profiles during both weight maintenance and weight loss weather condition. During weight maintenance, increases in LDL size and big LDL concentration are seen, sometimes at the expense of the more atherogenic modest LDL [43,51,61,62]. Similar responses are observed in LDL particle profiles during weight loss [55,63]. The plasma concentration of oxidized LDL has been shown to be unaffected by added cholesterol from eggs in the few studies where it was measured [51,55,61]. Additionally, several studies examining the furnishings of added cholesterol from eggs under weight maintenance and weight loss conditions accept shown increases in the size of HDL and the concentration of big HDL particles [55,62,63].

three.3. Effects of Dietary Cholesterol and/or Eggs on HDL Metabolism and Functionality

HDL is thought to be atheroprotective via its role in reverse cholesterol transport (RCT), as well as through antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities [64]. Dietary cholesterol feeding in mice has been shown to consequence in a compensatory consecration of RCT via HDL-related pathways [65]. Whether the reported increases in HDL-C and HDL particle size with dietary cholesterol and/or egg intake are improving RCT in humans is unclear. Multiple drug trials have failed to show a do good of raising HDL-C in CVD [66,67]. Notwithstanding, in that location are studies that evidence dietary cholesterol and/or eggs may affect markers of HDL functionality across HDL-C. Dietary cholesterol intake in a cohort of 1400 adults was found to be one of just a few dietary factors to independently predict serum paraoxonase-1 (PON1) arylesterase activity [68]. PON1 is a lipolactonase enzyme carried by HDL known to promote atheroprotection through preventing lipoprotein oxidation [69], inhibiting macrophage inflammation [seventy], and enhancing HDL-mediated cellular cholesterol efflux [71]. Interestingly, serum PON1 arylesterase activity was significantly increased in young, healthy adults with the consumption of iii eggs per 24-hour interval over 4 weeks [72]. Furthermore, increases in large HDL particle concentrations with egg intake accept ofttimes coincided with increases in the activity of lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) [45,46,54,55,72]. LCAT is an HDL-associated enzyme disquisitional for the maturation of HDL via conversion of free cholesterol to cholesteryl esters [73]. The mobilization of cholesterol from macrophages by HDL, termed cholesterol efflux capacity, has been shown in accomplice studies to be a significant predictor of CVD, contained of HDL-C and HDL particle concentrations [74,75]. Notably, when adults with metabolic syndrome consumed three eggs per day for 12 weeks during moderate carbohydrate restriction, the cholesterol efflux capacity of serum increased, whereas consumption of a yolk-free egg substitute had no issue [76]. Overall, the increased HDL-C commonly observed with dietary cholesterol feeding in humans appears to also coincide with improvements in other markers of HDL function. However, more than investigation into the effects of dietary cholesterol on HDL functionality in humans is warranted.

3.four. The Phospholipid Component of Eggs May Influence the Response to Dietary Cholesterol

Relative to other foods, eggs are a rich source of phospholipids, such every bit phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin (SM) [27,77]. The phospholipid component of egg yolk may impair intestinal cholesterol absorption, which has been demonstrated with both phosphatidylcholine and SM [77]. Dietary SM, in detail, has been shown to inhibit the assimilation of both cholesterol and fat in rodents [78,79]. The addition of SM to micelles inhibited cholesterol uptake in Caco-2 cells when it was used at increasing tooth ratios of SM:cholesterol (≥0.v:1) [80]. The ratio of SM:cholesterol in egg yolk is approximately 1:2–1:4, and therefore, may alter the response to dietary cholesterol found in eggs. Dietary SM intake has been shown extensively in rodents, and less then in humans, to reduce serum lipids [81]. We recently fed egg SM (0.1% due west/w diet) to male C57BL/6 mice that consumed a high fat, high cholesterol Western-type diet (60% kcal fatty, 0.two% cholesterol by weight) for 10 weeks [82]. The egg SM content of the diet was fed at a similar ratio to dietary cholesterol as it is institute in egg yolk. Compared to command mice fed the Western-blazon diet without SM, the mice fed egg SM had a 22% reduction in serum cholesterol, too as threescore% and 25% reductions in liver triglyceride and liver cholesterol, respectively. These mice fed egg SM were as well protected from numerous inflammatory and metabolic complications associated with obesity. Recently, Chung et al. [83] conducted an extensive written report on the effects of egg SM on atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein(apo) E−/− mice fed both grub and high fatty, high cholesterol diets. Chow-fed male person apoE−/− mice fed i.ii% (w/w diet) egg SM for 19 weeks were found to take reduced plaque size in aortic arches compared to command mice. Interestingly, serum TMAO concentrations were relatively unchanged even with this relatively high dose of egg SM, suggesting the phosphocholine moiety of egg SM is non readily bachelor for trimethylamine generation by gut microbiota. Thus, it is likely that TMAO does not contribute to the effects of egg SM on disease outcomes in creature studies. The reduction in aortic arch lesion size with egg SM feeding was actually abolished when mice were co-administered broad-spectrum antibiotics to deplete gut microbiota. These findings suggest that dietary SM may work via effects on gut microbiota, which is supported by a recent mouse study showing dietary SM altered gut microbiota in high fat nutrition-fed mice [84]. More research is warranted to better sympathize the furnishings of dietary SM on chronic disease progression, including determining whether such effects are solely dependent on inhibiting lipid absorption or due to other reported effects on gut microbiota and inflammation [85].

iv. Conclusions

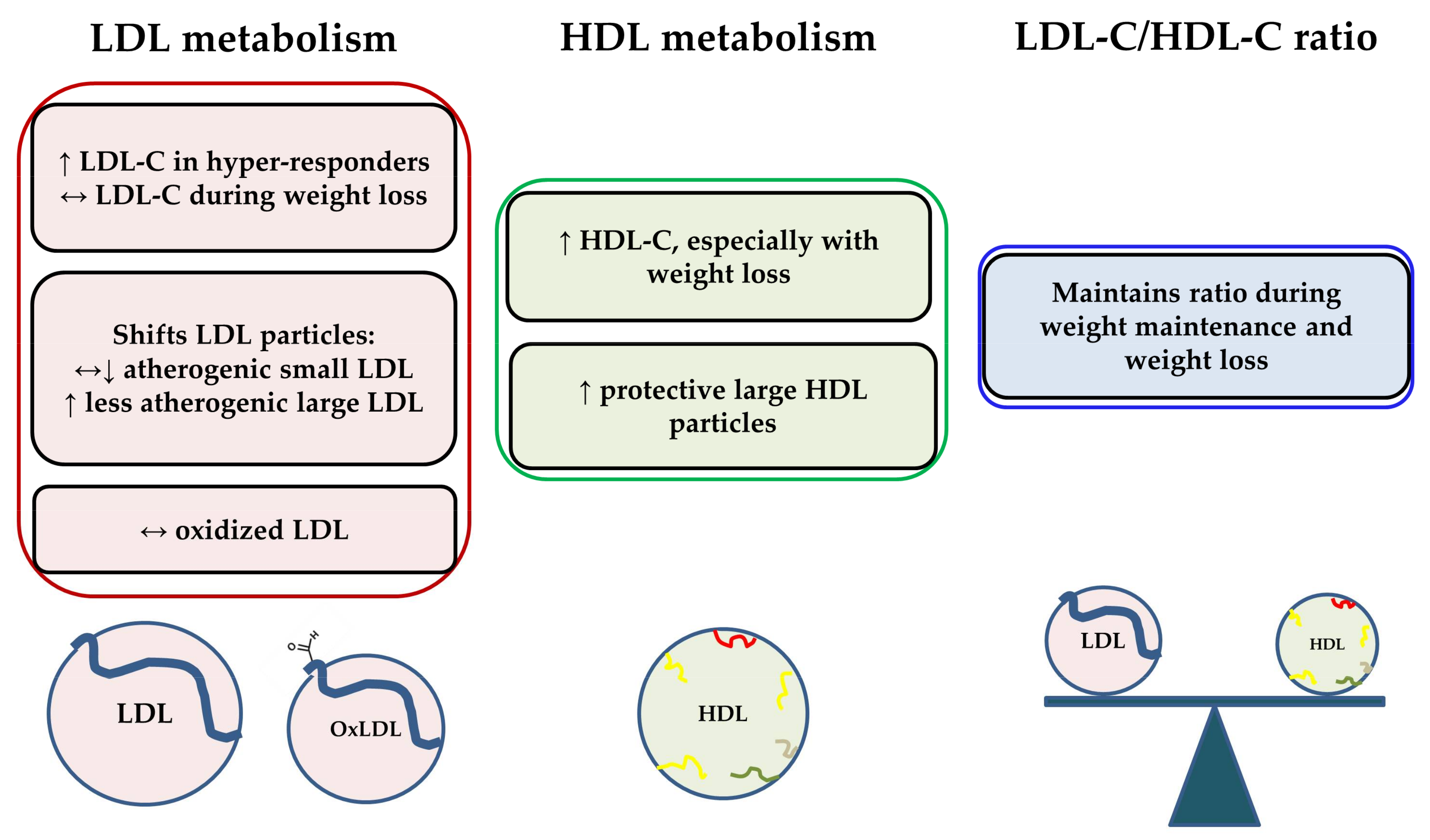

Effigy 1 summarizes the effects of consuming boosted cholesterol from eggs on LDL and HDL metabolism in recent clinical studies. Chronic daily egg intake does increment LDL-C to a certain extent in individuals classified as hyper-responders. Even so, LDL-C responses are typically minimal when eggs are consumed during weight loss conditions. Egg intake shifts LDL particles to the less detrimental, big LDL subclass, and does non announced to touch the levels of oxidized LDL. Egg intake also typically increases HDL-C and the concentration of large HDL, especially with weight loss. These changes announced to coincide with improvements in other markers of HDL function as well (e.grand., PON1, cholesterol efflux capacity, LCAT). The effect of egg intake on the LDL-C/HDL-C ratio is negligible during weight maintenance and weight loss weather condition. The human relationship between dietary cholesterol and/or egg intake and CVD risk in diabetics requires further investigation. However, egg intake in the context of insulin resistance and/or diabetes would non be expected to be detrimental due to changes in serum lipids, as serum lipid responses to additional dietary cholesterol are often diminished in clinical studies of insulin-resistant groups compared to leaner, more insulin-sensitive individuals. Overall, contempo intervention studies with eggs demonstrate that the additional dietary cholesterol does not negatively affect serum lipids, and in some cases, appears to better lipoprotein particle profiles and HDL functionality.

Author Contributions

Thou.L.F. contributed ideas, critical interpretation of data, and content of the manuscript. C.Due north.B. conducted the literature search, interpreted data, prepared the figure, wrote the manuscript, and had main responsibility for last content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Involvement

M.Fifty.F. and C.N.B. have received prior funding from the Egg Nutrition Center. The funding sponsors had no role in the estimation of data or the writing of the manuscript.

References

- Organization, W.H. Global Condition Study on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, R. Atherosclerosis—An inflammatory illness. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewington, S.; Whitlock, G.; Clarke, R.; Sherliker, P.; Emberson, J.; Halsey, J.; Qizilbash, North.; Peto, R.; Collins, R. Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by historic period, sexual activity, and blood pressure: A meta-analysis of private data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths. Lancet 2007, 370, 1829–1839. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gordon, D.J.; Probstfield, J.L.; Garrison, R.J.; Neaton, J.D.; Castelli, W.P.; Knoke, J.D.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Bangdiwala, Southward.; Tyroler, H.A. Loftier-density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiovascular affliction. 4 prospective american studies. Circulation 1989, 79, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, M.R.; Wald, Northward.J.; Rudnicka, A.R. Quantifying effect of statins on low density lipoprotein cholesterol, ischaemic heart disease, and stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2003, 326, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawber, T.R.; Moore, F.Due east.; Isle of man, G.V. Coronary heart disease in the framingham study. Am. J. Public Health Nations Health 1957, 47, four–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, G.V.; Pearson, Thou.; Gordon, T.; Dawber, T.R. Diet and cardiovascular disease in the framingham study. I. Measurement of dietary intake. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1962, xi, 200–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Classics in arteriosclerosis research: On experimental cholesterin steatosis and its significance in the origin of some pathological processes by N. Anitschkow and S. Chalatow, translated by Mary Z. Pelias, 1913. Arteriosclerosis 1983, 3, 178–182.

- U.S. Section of Agronomics, Agricultural Research Service. Nutrient Intakes from Food and Beverages: Mean Amounts Consumed Per Individual, past Gender and Age, What We Consume in America. NHANES 2013-2014. Available online: www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/fsrg (accessed on 22 January 2018).

- Keast, D.R.; Fulgoni, V.Fifty., 3rd; Nicklas, T.A.; O'Neil, C.Eastward. Food sources of energy and nutrients among children in the united states: National health and nutrition exam survey 2003–2006. Nutrients 2013, 5, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Neil, C.E.; Keast, D.R.; Fulgoni, Five.50.; Nicklas, T.A. Nutrient sources of energy and nutrients amid adults in the us: Nhanes 2003-2006. Nutrients 2012, 4, 2097–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shekelle, R.B.; Stamler, J. Dietary cholesterol and ischaemic heart affliction. Lancet 1989, i, 1177–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushi, L.H.; Lew, R.A.; Stare, F.J.; Ellison, C.R.; el Lozy, M.; Bourke, Chiliad.; Daly, 50.; Graham, I.; Hickey, North.; Mulcahy, R.; et al. Diet and xx-year mortality from coronary heart affliction. The ireland-boston diet-heart written report. N. Engl. J. Med. 1985, 312, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, Y.; Chen, 50.; Zhu, T.; Song, Y.; Yu, Thousand.; Shan, Z.; Sands, A.; Hu, F.B.; Liu, L. Egg consumption and risk of coronary eye disease and stroke: Dose-response meta-assay of prospective accomplice studies. BMJ 2013, 346, e8539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Shin, J.Y.; Xun, P.; Nakamura, Y.; He, K. Egg consumption in relation to risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: A systematic review and meta-assay. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virtanen, J.One thousand.; Mursu, J.; Virtanen, H.E.; Fogelholm, M.; Salonen, J.T.; Koskinen, T.T.; Voutilainen, South.; Tuomainen, T.P. Associations of egg and cholesterol intakes with carotid intima-media thickness and risk of incident coronary artery disease co-ordinate to apolipoprotein e phenotype in men: The kuopio ischaemic heart affliction risk factor study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, Southward.C.; Akesson, A.; Wolk, A. Egg consumption and run a risk of heart failure, myocardial infarction, and stroke: Results from 2 prospective cohorts. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Rimm, E.B.; Hu, F.B.; Albert, C.Yard.; Rexrode, K.M.; Manson, J.E.; Qi, L. Dietary phosphatidylcholine and take a chance of all-cause and cardiovascular-specific mortality among u.s.a. women and men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pihlajamaki, J.; Gylling, H.; Miettinen, T.A.; Laakso, M. Insulin resistance is associated with increased cholesterol synthesis and decreased cholesterol assimilation in normoglycemic men. J. Lipid Res. 2004, 45, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonen, P.; Gylling, H.; Howard, A.Due north.; Miettinen, T.A. Introducing a new component of the metabolic syndrome: Depression cholesterol absorption. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miettinen, T.A.; Gylling, H. Cholesterol absorption efficiency and sterol metabolism in obesity. Atherosclerosis 2000, 153, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Klipfell, E.; Bennett, B.J.; Koeth, R.; Levison, B.S.; Dugar, B.; Feldstein, A.E.; Britt, Due east.B.; Fu, X.; Chung, Y.K.; et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature 2011, 472, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.H.; Wang, Z.; Levison, B.Southward.; Koeth, R.A.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Hazen, S.L. Abdominal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular hazard. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1575–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiMarco, D.K.; Missimer, A.; Murillo, A.1000.; Lemos, B.S.; Malysheva, O.V.; Caudill, M.A.; Blesso, C.Northward.; Fernandez, M.L. Intake of upwards to 3 eggs/solar day increases hdl cholesterol and plasma choline while plasma trimethylamine-n-oxide is unchanged in a healthy population. Lipids 2017, 52, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Missimer, A.; Fernandez, M.L.; DiMarco, D.M.; Norris, Thousand.H.; Blesso, C.Due north.; Murillo, A.G.; Vergara-Jimenez, Grand.; Lemos, B.S.; Medina-Vera, I.; Malysheva, O.Five.; et al. Compared to an oatmeal breakfast, two eggs/24-hour interval increased plasma carotenoids and choline without increasing trimethyl amine n-oxide concentrations. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2018, 37, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, C.Eastward.; Taesuwan, S.; Malysheva, O.V.; Bender, East.; Tulchinsky, N.F.; Yan, J.; Sutter, J.L.; Caudill, 1000.A. Trimethylamine-due north-oxide (tmao) response to brute source foods varies among healthy immature men and is influenced by their gut microbiota limerick: A randomized controlled trial. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blesso, C.North. Egg phospholipids and cardiovascular wellness. Nutrients 2015, 7, 2731–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, C.East.; Caudill, M.A. Trimethylamine-n-oxide: Friend, foe, or simply defenseless in the cross-fire? Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 28, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, S.; Raman, One thousand.; Vishwanathan, R.; Jacques, P.F.; Johnson, E.J. Dietary cholesterol and cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 276–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, Due west.H.; McNamara, D.J.; Tosca, G.A.; Smith, B.T.; Gaines, J.A. Plasma lipid and lipoprotein responses to dietary fat and cholesterol: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 65, 1747–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, D.J.; Kolb, R.; Parker, T.S.; Batwin, H.; Samuel, P.; Dark-brown, C.D.; Ahrens, E.H., Jr. Heterogeneity of cholesterol homeostasis in man. Response to changes in dietary fatty quality and cholesterol quantity. J. Clin. Investig. 1987, 79, 1729–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosner, Thousand.S.; Lange, L.G.; Stenson, W.F.; Ostlund, R.Eastward., Jr. Pct cholesterol assimilation in normal women and men quantified with dual stable isotopic tracers and negative ion mass spectrometry. J. Lipid Res. 1999, 40, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.S.; Connor, W.Eastward. The long term effects of dietary cholesterol upon the plasma lipids, lipoproteins, cholesterol absorption, and the sterol balance in man: The demonstration of feedback inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis and increased bile acid excretion. J. Lipid Res. 1980, 21, 1042–1052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ikonen, E. Cellular cholesterol trafficking and compartmentalization. Nat. Rev. Mol. Prison cell Biol. 2008, ix, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, D.J. The touch on of egg limitations on coronary center disease risk: Do the numbers add up? J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2000, 19, 540S–548S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mensink, R.P.; Zock, P.Fifty.; Kester, A.D.; Katan, 1000.B. Effects of dietary fat acids and carbohydrates on the ratio of serum total to hdl cholesterol and on serum lipids and apolipoproteins: A meta-analysis of 60 controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 77, 1146–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mensink, R.P.; Katan, Yard.B. Consequence of dietary fatty acids on serum lipids and lipoproteins. A meta-analysis of 27 trials. Arterioscler. Thromb. 1992, 12, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keys, A.; Anderson, J.T.; Grande, F. Serum cholesterol response to changes in the diet: Ii. The effect of cholesterol in the diet. Metabolism 1965, 14, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katan, M.B.; Beynen, A.C. Characteristics of human hypo- and hyperresponders to dietary cholesterol. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1987, 125, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, F., Jr. Normal plasma cholesterol in an 88-year-old human who eats 25 eggs a day. Mechanisms of adaptation. Northward. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 324, 896–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knopp, R.H.; Retzlaff, B.; Fish, B.; Walden, C.; Wallick, Southward.; Anderson, M.; Aikawa, K.; Kahn, S.E. Effects of insulin resistance and obesity on lipoproteins and sensitivity to egg feeding. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003, 23, 1437–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herron, K.L.; McGrane, M.M.; Waters, D.; Lofgren, I.E.; Clark, R.M.; Ordovas, J.Yard.; Fernandez, M.L. The abcg5 polymorphism contributes to individual responses to dietary cholesterol and carotenoids in eggs. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 1161–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballesteros, K.North.; Cabrera, R.M.; Saucedo Mdel, S.; Fernandez, 1000.L. Dietary cholesterol does not increment biomarkers for chronic disease in a pediatric population from northern mexico. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, lxxx, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herron, Thousand.L.; Vega-Lopez, South.; Conde, M.; Ramjiganesh, T.; Roy, S.; Shachter, Due north.Due south.; Fernandez, Chiliad.L. Pre-menopausal women, classified as hypo- or hyperresponders, do non alter their ldl/hdl ratio post-obit a high dietary cholesterol claiming. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2002, 21, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herron, K.Fifty.; Vega-Lopez, S.; Conde, K.; Ramjiganesh, T.; Shachter, N.South.; Fernandez, Thou.L. Men classified as hypo- or hyperresponders to dietary cholesterol feeding exhibit differences in lipoprotein metabolism. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, C.M.; Zern, T.L.; Forest, R.J.; Shrestha, S.; Aggarwal, D.; Sharman, Thousand.J.; Volek, J.S.; Fernandez, M.L. Maintenance of the ldl cholesterol:Hdl cholesterol ratio in an elderly population given a dietary cholesterol claiming. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 2793–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, One thousand.L.; Webb, D. The ldl to hdl cholesterol ratio every bit a valuable tool to evaluate coronary heart disease risk. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2008, 27, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullen, P.; Schulte, H.; Assmann, Grand. The munster heart report (procam): Full mortality in middle-anile men is increased at low total and ldl cholesterol concentrations in smokers but not in nonsmokers. Circulation 1997, 96, 2128–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knopp, R.H.; Retzlaff, B.M.; Walden, C.E.; Dowdy, A.A.; Tsunehara, C.H.; Austin, M.A.; Nguyen, T. A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial of the effects of ii eggs per day in moderately hypercholesterolemic and combined hyperlipidemic subjects taught the ncep stride i diet. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1997, 16, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vishwanathan, R.; Goodrow-Kotyla, E.F.; Wooten, B.R.; Wilson, T.A.; Nicolosi, R.J. Consumption of 2 and 4 egg yolks/d for five wk increases macular pigment concentrations in older adults with depression macular pigment taking cholesterol-lowering statins. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, xc, 1272–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballesteros, M.Due north.; Valenzuela, F.; Robles, A.E.; Artalejo, E.; Aguilar, D.; Andersen, C.J.; Valdez, H.; Fernandez, Grand.L. Ane egg per twenty-four hour period improves inflammation when compared to an oatmeal-based breakfast without increasing other cardiometabolic take chances factors in diabetic patients. Nutrients 2015, 7, 3449–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, N.R.; Caterson, I.D.; Sainsbury, A.; Denyer, G.; Fong, M.; Gerofi, J.; Baqleh, K.; Williams, Thousand.H.; Lau, North.Due south.; Markovic, T.P. The upshot of a high-egg nutrition on cardiovascular risk factors in people with type 2 diabetes: The diabetes and egg (diabegg) written report-a 3-mo randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harman, N.Fifty.; Leeds, A.R.; Griffin, B.A. Increased dietary cholesterol does not increment plasma low density lipoprotein when accompanied by an energy-restricted diet and weight loss. Eur. J. Nutr. 2008, 47, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutungi, G.; Ratliff, J.; Puglisi, Thousand.; Torres-Gonzalez, Chiliad.; Vaishnav, U.; Leite, J.O.; Quann, East.; Volek, J.S.; Fernandez, M.L. Dietary cholesterol from eggs increases plasma hdl cholesterol in overweight men consuming a saccharide-restricted diet. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blesso, C.N.; Andersen, C.J.; Barona, J.; Volek, J.S.; Fernandez, M.Fifty. Whole egg consumption improves lipoprotein profiles and insulin sensitivity to a greater extent than yolk-free egg substitute in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Metabolism 2013, 62, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, K.L.; Clifton, P.M.; Noakes, G. Egg consumption as part of an energy-restricted loftier-protein nutrition improves claret lipid and blood glucose profiles in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 105, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman, D.Due south.; Otvos, J.D.; Jeyarajah, E.J.; Barboriak, J.J.; Anderson, A.J.; Walker, J.A. Relation of lipoprotein subclasses equally measured past proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy to coronary avenue illness. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1998, xviii, 1046–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora, S.; Otvos, J.D.; Rifai, N.; Rosenson, R.S.; Buring, J.E.; Ridker, P.M. Lipoprotein particle profiles past nuclear magnetic resonance compared with standard lipids and apolipoproteins in predicting incident cardiovascular disease in women. Circulation 2009, 119, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tribble, D.L.; Rizzo, Thousand.; Chait, A.; Lewis, D.Chiliad.; Blanche, P.J.; Krauss, R.G. Enhanced oxidative susceptibility and reduced antioxidant content of metabolic precursors of small, dense depression-density lipoproteins. Am. J. Med. 2001, 110, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witztum, J.L.; Steinberg, D. Part of oxidized depression density lipoprotein in atherogenesis. J. Clin. Investig. 1991, 88, 1785–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herron, K.L.; Lofgren, I.East.; Sharman, M.; Volek, J.South.; Fernandez, M.L. High intake of cholesterol results in less atherogenic low-density lipoprotein particles in men and women independent of response nomenclature. Metabolism 2004, 53, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, C.M.; Waters, D.; Clark, R.M.; Contois, J.H.; Fernandez, Thou.L. Plasma ldl and hdl characteristics and carotenoid content are positively influenced by egg consumption in an elderly population. Nutr. Metab. 2006, iii, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutungi, Chiliad.; Waters, D.; Ratliff, J.; Puglisi, M.; Clark, R.M.; Volek, J.S.; Fernandez, M.L. Eggs distinctly modulate plasma carotenoid and lipoprotein subclasses in adult men post-obit a saccharide-restricted nutrition. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2010, 21, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rye, K.A.; Barter, P.J. Cardioprotective functions of hdls. J. Lipid Res. 2014, 55, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escola-Gil, J.C.; Llaverias, Chiliad.; Julve, J.; Jauhiainen, M.; Mendez-Gonzalez, J.; Blanco-Vaca, F. The cholesterol content of western diets plays a major role in the paradoxical increase in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and upregulates the macrophage reverse cholesterol transport pathway. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 2493–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingwell, B.A.; Chapman, Chiliad.J.; Kontush, A.; Miller, Northward.Eastward. Hdl-targeted therapies: Progress, failures and futurity. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toth, P.P.; Barylski, M.; Nikolic, D.; Rizzo, M.; Montalto, G.; Banach, M. Should low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (hdl-c) be treated? Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 28, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.S.; Burt, A.A.; Ranchalis, J.E.; Richter, R.J.; Marshall, J.One thousand.; Nakayama, K.S.; Jarvik, Due east.R.; Eintracht, J.F.; Rosenthal, Eastward.A.; Furlong, C.East.; et al. Dietary cholesterol increases paraoxonase one enzyme activeness. J. Lipid Res. 2012, 53, 2450–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, D.M.; Xia, Y.R.; Wang, X.P.; Miller, East.; Castellani, L.W.; Subbanagounder, K.; Cheroutre, H.; Faull, Thou.F.; Berliner, J.A.; Witztum, J.L.; et al. Combined serum paraoxonase knockout/apolipoprotein e knockout mice exhibit increased lipoprotein oxidation and atherosclerosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 17527–17535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aharoni, Due south.; Aviram, K.; Fuhrman, B. Paraoxonase 1 (pon1) reduces macrophage inflammatory responses. Atherosclerosis 2013, 228, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenblat, M.; Vaya, J.; Shih, D.; Aviram, M. Paraoxonase 1 (pon1) enhances hdl-mediated macrophage cholesterol efflux via the abca1 transporter in clan with increased hdl binding to the cells: A possible role for lysophosphatidylcholine. Atherosclerosis 2005, 179, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiMarco, D.1000.; Norris, Thousand.H.; Millar, C.Fifty.; Blesso, C.North.; Fernandez, Yard.L. Intake of up to three eggs per 24-hour interval is associated with changes in hdl function and increased plasma antioxidants in healthy, immature adults. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rousset, X.; Shamburek, R.; Vaisman, B.; Amar, M.; Remaley, A.T. Lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase: An anti- or pro-atherogenic factor? Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2011, 13, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khera, A.Five.; Cuchel, M.; de la Llera-Moya, M.; Rodrigues, A.; Shush, M.F.; Jafri, K.; French, B.C.; Phillips, J.A.; Mucksavage, Thou.Fifty.; Wilensky, R.L.; et al. Cholesterol efflux capacity, high-density lipoprotein role, and atherosclerosis. Due north. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohatgi, A.; Khera, A.; Berry, J.D.; Givens, E.G.; Ayers, C.R.; Wedin, K.E.; Neeland, I.J.; Yuhanna, I.S.; Rader, D.R.; de Lemos, J.A.; et al. Hdl cholesterol efflux chapters and incident cardiovascular events. Due north. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 2383–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, C.J.; Blesso, C.N.; Lee, J.; Barona, J.; Shah, D.; Thomas, Grand.J.; Fernandez, M.L. Egg consumption modulates hdl lipid composition and increases the cholesterol-accepting capacity of serum in metabolic syndrome. Lipids 2013, 48, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohn, J.S.; Kamili, A.; Wat, E.; Chung, R.W.; Tandy, S. Dietary phospholipids and intestinal cholesterol absorption. Nutrients 2010, 2, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noh, S.Thousand.; Koo, S.I. Egg sphingomyelin lowers the lymphatic assimilation of cholesterol and blastoff-tocopherol in rats. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 3571–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noh, S.Thou.; Koo, S.I. Milk sphingomyelin is more effective than egg sphingomyelin in inhibiting intestinal assimilation of cholesterol and fat in rats. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 2611–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, D.; Ohlsson, Fifty.; Ling, Westward.; Nilsson, A.; Duan, R.D. Generating ceramide from sphingomyelin by alkaline sphingomyelinase in the gut enhances sphingomyelin-induced inhibition of cholesterol uptake in caco-2 cells. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2010, 55, 3377–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, M.H.; Blesso, C.Northward. Dietary sphingolipids: Potential for management of dyslipidemia and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, G.H.; Porter, C.M.; Jiang, C.; Millar, C.L.; Blesso, C.N. Dietary sphingomyelin attenuates hepatic steatosis and adipose tissue inflammation in high-fat-diet-induced obese mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2017, 40, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, R.W.Southward.; Wang, Z.; Bursill, C.A.; Wu, B.J.; Barter, P.J.; Rye, 1000.A. Effect of long-term dietary sphingomyelin supplementation on atherosclerosis in mice. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, G.H.; Jiang, C.; Ryan, J.; Porter, C.M.; Blesso, C.N. Milk sphingomyelin improves lipid metabolism and alters gut microbiota in high fat diet-fed mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 30, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, G.H.; Blesso, C.N. Dietary and endogenous sphingolipid metabolism in chronic inflammation. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Effigy i. Summary of furnishings of consuming additional cholesterol from eggs on LDL and HDL metabolism in recent clinical studies. OxLDL = oxidized LDL; ↔ = no alter relative to control, ↑ = increase relative to control; ↓ = decrease relative to control.

Effigy 1. Summary of effects of consuming additional cholesterol from eggs on LDL and HDL metabolism in recent clinical studies. OxLDL = oxidized LDL; ↔ = no change relative to control, ↑ = increase relative to control; ↓ = decrease relative to control.

Table i. Effects of additional dietary cholesterol from egg intake on serum lipids during weight maintenance: healthy and hyperlipidemic populations.

Table 1. Effects of additional dietary cholesterol from egg intake on serum lipids during weight maintenance: healthy and hyperlipidemic populations.

| Study/Population | Design | # Days | LDL-C | HDL-C | LDL-C/HDL-C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children | |||||

| Ballesteros et al. 2004 [43]; Healthy boys and girls | Crossover (n = 54): two eggs per day (518 mg cholesterol) vs. egg substitute | 30 | Hyper-: +25% Hypo-: ↔ | Hyper-: +10% Hypo-: ↔ | ↔ |

| Adults | |||||

| Herron et al. 2002 [44]; Healthy women | Crossover (n = 51): three eggs per day (640 mg cholesterol) vs. egg substitute | thirty | Hyper-: +xx% Hypo-: ↔ | Hyper-: +12% Hypo-: ↔ | ↔ |

| Herron et al. 2003 [45]; Healthy men | Crossover (due north = 40): 3 eggs per day (640 mg cholesterol) vs. egg substitute | 30 | Hyper-: +30% Hypo-: ↔ | Hyper-: +viii% Hypo-: ↔ | Hyper-: + 22% Hypo-: ↔ |

| Greene et al. 2005 [46]; Salubrious older adults | Crossover (northward = 42): 3 eggs per day (640 mg cholesterol) vs. egg substitute | 30 | Women: +ten% Men: +two% | Women: +3% Men: +10% | ↔ |

| Knopp et al. 2003 [41]; Insulin-sensitive | Crossover (n = 65): 4 eggs per day (850 mg cholesterol) vs. egg substitute | 28 | +7% | +7% | ND * |

| Hyperlipidemic | |||||

| Knopp et al. 1997 [49]; Hypercholesterolemic (HC) and combined hyperlipidemic (CHL) men/women | Parallel: 2 eggs per day (425 mg cholesterol) (HC: northward = 44; CHL: n = 31) vs. egg substitute (HC: due north = 35; CHL: n = 21) | 84 | HC: ↔ CHL: +8% from baseline | HC: +8% from baseline CHL: +7% from baseline | ND |

| Vishwanathan et al. 2009 [fifty]; Statin-taking older adults | Crossover (n = 52): 2 or 4 eggs per twenty-four hours (~400–800 mg cholesterol) vs. egg exclusion | 35 | 2 eggs: ↔ 4 eggs: ↔ | ii eggs: +5% 4 eggs: +5% | ND |

Tabular array 2. Effects of additional dietary cholesterol from egg intake on serum lipids during weight maintenance: insulin-resistant and diabetic populations.

Table 2. Furnishings of additional dietary cholesterol from egg intake on serum lipids during weight maintenance: insulin-resistant and diabetic populations.

| Report/Population | Design | # Days | LDL-C | HDL-C | LDL-C/HDL-C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin-resistant | |||||

| Knopp et al. 2003 [41]; Insulin-resistant (IR) and obese insulin-resistant (OIR) | Crossover (IR: n = 75; OIR: n = 57): 4 eggs per day (850 mg cholesterol) vs. egg substitute | 28 | IR: +6% OIR: ↔ | IR: +6% OIR: +6% | ND * |

| Diabetic | |||||

| Ballesteros et al. 2015 [51]; Diabetic patients | Crossover (due north = 29): 1 egg per twenty-four hours (250 mg cholesterol) vs. oatmeal breakfast | 35 | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ |

| Fuller et al. 2015 [52]; Diabetic patients | Parallel: High egg (12 eggs/week; ~300–350 mg cholesterol/twenty-four hours) (due north = 72) vs. low egg (<2 eggs/week) (due north = 68) | 42 | ↔ | ↔ | ND |

Table 3. Effects of additional dietary cholesterol from egg intake on serum lipids during weight loss.

Table iii. Furnishings of additional dietary cholesterol from egg intake on serum lipids during weight loss.

| Study/Population | Design | # Days | LDL-C | HDL-C | LDL-C/HDL-C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harman et al. 2008 [53]; Men/women | Parallel: 2 eggs per day (~400 mg cholesterol) (north = 24) vs. egg exclusion (north = 21) | 84 | ↔ | ↔ | ND * |

| Mutungi et al. 2008 [54]; Overweight/obese men | Parallel: 3 eggs per 24-hour interval (640 mg cholesterol) (n = fifteen) vs. egg substitute (n = xiii) | 84 | ↔ | +25% from baseline | ↔ |

| Pearce et al. 2011 [56]; Diabetic patients | Parallel: 2 eggs per day (590 mg cholesterol/day) (n = 31) vs. egg exclusion (213 mg cholesterol/day) (northward = 34) | 84 | ↔ | Eggs +2% from baseline, egg exclusion −6% from baseline | ↔ |

| Blesso et al. 2013 [55]; Metabolic syndrome men/women | Parallel: three eggs per day (640 mg cholesterol) (n = twenty) vs. egg substitute (northward = 17) | 84 | ↔ | +17% from baseline | ↓ |

Table 4. Effects of additional dietary cholesterol from egg intake on lipoprotein particle profiles.

Table 4. Furnishings of additional dietary cholesterol from egg intake on lipoprotein particle profiles.

| Study/Population | Design | # Days | LDL Particles | Oxidized LDL | HDL Particles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight maintenance | |||||

| Ballesteros et al. 2004 [43]; Salubrious children | Crossover (north = 54): ii eggs per day (518 mg cholesterol) vs. egg substitute | xxx | ↑Big LDL (+31% LDL-1 in hyper-) ↓Pocket-sized LDL (−38% LDL-3 in hyper-) ↑LDL size | ND * | ND |

| Herron et al. 2004 [61]; Healthy men/women | Crossover (north = 52): 3 eggs per solar day (640 mg cholesterol) vs. egg substitute | xxx | ↑Large LDL (+13% LDL-1, +xxx% LDL-2 in women hyper-) | ↔ | ND |

| Greene et al. 2006 [62]; Salubrious elderly men/women | Crossover (n = 42): 3 eggs per day (640 mg cholesterol) vs. egg substitute | 30 | ↑Large LDL (+30% from baseline in hyper-) | ND | ↑Large HDL (+23% from baseline in hyper-) ↑HDL size |

| Ballesteros et al. 2015 [51]; Diabetic patients | Crossover (northward = 29): 1 egg per day (250 mg cholesterol) vs. oatmeal breakfast | 35 | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ |

| Weight loss | |||||

| Mutungi et al. 2010 [63]; Overweight/obese men | Parallel: 3 eggs per 24-hour interval (640 mg cholesterol) (north = 15) vs. egg substitute (n = xiii) | 84 | ↑Large LDL (+42% from baseline) | ND | ↑Large HDL (+52% from baseline) ↑HDL size |

| Blesso et al. 2013 [55]; Metabolic syndrome men/women | Parallel: 3 eggs per day (640 mg cholesterol) (n = 20) vs. egg substitute (n = 17) | 84 | ↑Big LDL (+22% from baseline) | ↔ | ↑Large HDL (+30% from baseline) ↑HDL size |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access commodity distributed under the terms and atmospheric condition of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC By) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/iv.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/10/4/426/htm

0 Response to "Effects of Dietary Cholesterol on Serum Cholesterol a Meta-analysis and Review"

Enregistrer un commentaire